Close your eyes and imagine a typical city street. What do you see?

For most of us it’s a variation of a familiar scene: two lanes of automobile traffic most likely flanked by a row of densely parked cars on either side. Confined to the periphery, narrow sidewalks accommodate the vast majority of human activity performed by pedestrians, joggers, tourists, commuters, parents, pet owners, municipal workers and street vendors.

These are the city streets much of the world has come to know and accept over the past 100 years as urban living has progressively become defined by smog, combustion engines and tens of millions of square meters of car parking. It’s time for that to end.

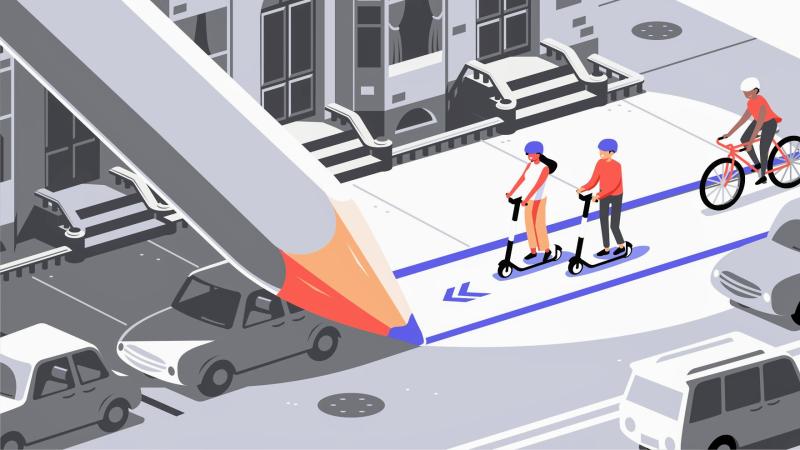

The post-pandemic 21st century is emerging as the era of the Third Lane—an innovative new way to use public space that disrupts our conventional, bidirectional norms.

Of course, on its surface the concept appears straightforward. By eliminating car parking and narrowing automobile lanes we can create the space necessary to accommodate lightweight, human sized micromobility vehicles such as electric scooters.

Once you better understand its implications, however, the Third Lane takes on a new level of significance that redefines the way we understand cities and urban public space altogether.

The Third Lane and Increased Mobility

For one, the Third Lane represents the freedom of physical mobility. We’ve long known that bikes and scooters—vehicles built to human scale—travel faster through cities than cars and motorcycles. They’re lighter, nimbler and more streamlined, making them significantly less susceptible to the traffic congestion that’s become so prevalent on city streets. They’re also much easier to park.

Protected micromobility infrastructure increases these advantages by safely separating the large and cumbersome vehicles from the small and agile ones. When cities prioritize the Third Lane, they’re investing in increased freedom of movement at a speed and scale designed for compact urban environments.

The Third Lane and Economic Opportunity

Prioritizing the Third Lane does more than just improve mobility, however. It also benefits local economies and small businesses in a number of ways, the first of which being perhaps the most evident.

Micromobility riders frequently travel to and from local shops and restaurants. We know this because, at Bird, approximately 50% of our riders surveyed indicated that the purpose of their most recent trip was dining or shopping. Moreover, more than 70% of those riders said that they were more likely to visit the establishment because of Bird. We see this trend consistently in cities around the world: when there are Birds outside, there are customers inside.

In conjunction with micromobility services, the Third Lane also connects riders to employment opportunities. It does this not only by increasing the accessibility of public transit stops, but by providing new mobility options and safe, expedient travel routes in areas traditionally underserved by public transit altogether. Researchers in Chicago, for example, found that e-scooters gave individuals access to 16% more jobs within a 30 minute radius compared to walking or transit alone. In Miami, a similar study found that 40% more jobs were reachable without lengthening current commute times thanks to micromobility.

Perhaps the most interesting way the Third Lane impacts local economies, however, has nothing to do with the lane itself. Instead, it’s connected to the same guiding principle of reclaiming public space. As we’ve seen in cities from San Francisco to Marseille, policy makers are repurposing streets and sidewalks in response to COVID-19, allowing restaurant patrons ample room to properly social distance. The results have been almost universally lauded as joyless parking spaces have been converted into lively centers of commerce and entertainment.

The Third Lane is an invitation to rethink urban streets, taking them away from cars and giving them back to the people and businesses that give life to our cities.

The Third Lane and Social Equity

Beyond efficiencies and economics, however, the Third Lane’s most prolific benefit is its inherent potential to promote social equity. We’ve already discussed how safe access to jobs and public transit increase when micromobility services and infrastructure are in place—but there’s more to it than that.

Car ownership, particularly in the US, is still closely connected to income. In general, the more money you make, the more likely you are to own a car (or two). Thus city streets dedicated solely to automobile traffic and car parking only serve to further isolate low-income neighborhoods and underserved populations. That can no longer be tolerated.

A recent study published in Transportation Research: Part A found that not only are electric scooters used more for transportation than for recreation, but they’re significantly more appealing to new riders who identify as non-white as well. That’s an encouraging start, and it highlights the potential for e-scooters not only to appeal to a wider swath of the population but to help level the urban mobility playing field for everyone. The only critical component missing is a protected, prioritized Third Lane in which to ride them.

For these reasons, and many more, it’s imperative that cities use the current health crisis as an opportunity to rethink conventional mobility norms and reclaim valuable urban street space. As the era of car dominated cities takes its inevitable place in the rear view mirror, the future of sustainable, equitable urban transportation is moving decisively into the Third Lane.

Travis VanderZanden is the founder and CEO of Bird